Presented at The Society for the Study of Early Christianity Conference, ‘The Early Church Unfolds: People, Places and Potential’, Robert Menzies College, Macquarie University, 4 May 2019. First published RTR 78, no. 2 (2018).

I had always assumed that from Persian times, Aramaic had been the koinē tongue of Palestine in the era of the New Testament, and further, that the disciples memorised Jesus’ words in that language and passed them on to others, who in turn rendered them into the Greek of the Gospels. In the course of writing a book soon to appear,1Paul Barnett, Making the Gospels: Mystery or Conspiracy? (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2019). I changed my mind about this, for reasons I will mention a little later. It was a ‘light bulb’ moment.

Contents

1. G. Scott Gleaves

After the book was almost ready to send to the publisher, I came across a book that I did not have time to read. G. Scott Gleaves makes a serious case that Jesus did, in fact, speak Greek.2G. Scott Gleaves, Did Jesus Speak Greek? (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2015). Among those who have supported this, to whom Gleaves refers throughout, are Stanley Porter, Nigel Turner and J. N. Sevenster, and among older scholars, Thomas Abbott and Edward Grinfield. Alternatively, advocates for Aramaic originals of the Gospels, whom Gleaves quotes, are Gustav Dalman, Emil Schürer, Joseph Fitzmyer, Maurice Casey, Matthew Black, and Charles Fox Burney.

Gleaves quotes Porter, who identifies eight episodes in the Gospels where Jesus’ conversation would have been in Greek, the best-known examples of which are with the Syrophoenician woman, with a Centurion, and with Pontius Pilate. He establishes that the text of Isa 61:1–3 that Jesus read in the synagogue was from the Septuagint, that is, the Greek version. If Gleaves is correct, it means not only that Jesus read Greek but also that the synagogue members in Nazareth understood Greek. He goes so far as to argue that it was the Septuagint that was read in the synagogues in Galilee.

Gleaves’ argument can be summarised as follows. First, Galilee was surrounded by cities that were culturally and linguistically Greek.

- Cities established by the Seleucids: Pella, Gadara, Hippos, Dion, Philotera

- Cities established by Herod Philip: Caesarea Philippi, Bethsaida

- Cities founded or re-founded by Herod Antipas: Sepphoris, Tiberias

- Jesus’ home, Nazareth, was close to Caesarea Maritima, Dora, Ptolemais, Tiberias, Sepphoris.

Secondly, several of Jesus twelve disciples had Greek names. These are Simon, Andrew, and Philip.

Thirdly, the writers of the New Testament were Jews, so these are Jews who wrote Greek. Greaves, following Turner, explains the Semitic flavour of the Greek in the Gospels as due not to translations of Aramaic originals, but ‘Semitic’ Greek. Greaves quotes several linguistic experts who reject the idea that the Greek of the Gospels is a back translation of Aramaic originals.

Fourthly, the widespread currency of Greek is confirmed by archaeological remains:

- Of the twenty-nine Mt Olivet ossuaries, eleven are Greek.

- The Theodoret Inscription in Jerusalem

- The Letter of bar Kochba

- The Temple warning.

Fifthly, there is the powerful presence of the Septuagint in the New Testament. Of the 350 quotations of the Old Testament in the New Testament, only 50 do not come from the Septuagint. In the Semitic sounding Apocalypse, the Old Testament echoes are surprisingly Septuagint-based.

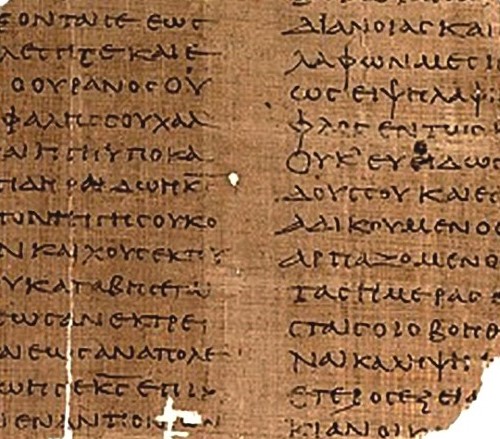

Sixthly, there are thousands of manuscripts or part manuscripts of the New Testament which are in Greek. There is not even one surviving Aramaic manuscript of the NT.

Seventhly, certain aspects of the Gospels only make sense if based on a Greek original. For example, σὺ εἶ Πέτρος, καὶ ἐπὶ ταύτῃ τῇ πέτρᾳ οἰκοδομήσω μου τὴν ἐκκλησίαν (‘You are Peter, and upon this rock, I will build my church’, Matt 16:18). The pun only works in Greek, where Petros (Peter) is masculine, and petra (rock) is feminine. The former means ‘rock’, whereas the usage of the latter in the Septuagint points to foundational bedrock. The truth Peter spoke—that Jesus is the Christ—is the bedrock foundation of Christianity. Gleaves argues that Jesus’ wordplay works in Greek but not in an Aramaic original.

This is Gleaves’s argument, which, as I said, I did not have in front of me when I wrote the book in question. There was, however, some overlap in the data that was marshalled. I noted the following.

Greek was widely spoken in Judea and Jerusalem. Funerary remains in and around Jerusalem frequently bear the Greek language. Martin Hengel went so far as to describe Jerusalem as a ‘Greek city’.3Martin Hengel, The Pre-Christian Paul (London: SCM, 1991), 54–57. He draws attention to the ‘Hellenists’ (Greek-speaking Jewish émigrés) living in Jerusalem as a well-established point in the book of Acts, and indicates that one-third of inscriptions in Jerusalem are in Greek.4Hengel, The Pre-Christian Paul, 54–57, who goes so far as to assert that Jerusalem was a ‘Greek city’ (54). Also, he argues that many Aramaic speaking indigenous Jews ‘had a good command’ of Greek. Hengel is an authority on the Hellenisation of Palestine under Ptolemaic and Seleucid influence.

The rival missionaries from Jerusalem who came to Corinth to displace Paul (in c. AD 56) excelled in public speaking and rhetoric (2 Cor 11:5–6; cf. 2:17), which would have been in Greek. The linguistic skill of these ‘super-apostles’, as Paul calls them, provides indirect evidence for the currency of the Greek language and education in Jerusalem.5It was said that Rabban Gamaliel II (who flourished in the late first into the second century) had one thousand students, five hundred of whom studied the Torah and five hundred who studied Greek wisdom. See L. Feldman, Jew and Gentile in the Ancient World (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 37.

The evidence of Greek usage in the north is important. Jesus travelled extensively in Hellenised regions to the north and east of Galilee where Greek was dominant. Galilee was ringed with Greek-speaking city-states: Tyre and Sidon to the northwest; Hippos and Gadara to the east; Scythopolis to the south. Sepphoris and Tiberias, the major cities of the tetrarchy of Galilee, were culturally Hellenistic.

Buying and selling in Galilee depended on a capacity to understand Greek, due to travellers streaming along the Via Maris that passed through Galilee. Likewise, the proximity of nearby city-states to Galilee implied travel to and from them to buy and to sell. The degree to which Palestine had been Hellenised is evident in the inscriptions and papyri from that era, including even such intensely Jewish centres as Qumran, Masada, Muraba’at, and Jerusalem itself.6Millard, Reading and Writing, 102–117.

Three of the disciples, Philip, Simon and Andrew, had Greek names and came from Bethsaida in Gaulanitis, a Greek-speaking tetrarchy. This was the obvious reason that Philip was sought out by some ‘Greeks’ who wanted to meet Jesus—and why he quickly involved Andrew (John 12:20–22).7On the points made here, see Markus Bockmuehl, The Remembered Peter in Ancient Reception and Modern Debate, WUNT 262 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2010), 164–165, 167, 184–185.

Many believe that Peter’s amanuensis, Silvanus, shaped the language in 1 Peter, a view to which I subscribe (1 Pet 5:12). Silvanus (also known as Silas in Acts) was an accomplished scholar with superior skills in the Greek language. He was also a Roman citizen (Acts 16:37). Since Silvanus was from Jerusalem, it is another reason to believe in the high level of Greek usage at that time in the Holy City. The same holds true for John Mark, who was a competent writer of Greek, with an understanding of Aramaic and Latin (as revealed by his numerous Latinisms in the Gospel of Mark). Not least, Paul, a Jerusalemite from his early teens, spoke Aramaic and was an accomplished writer of Greek, and most likely also Latin (being a Roman citizen).

Aramaic and Greek were both spoken in the Land of Israel

In summary, I noted that based on current research, it can be said that Aramaic and Greek were both spoken in the Land of Israel in the era of Jesus. No doubt there were pockets where one language was more concentrated than the other. At the same time, however, it is likely that many communities were fluent in spoken Aramaic and spoken Greek. To this day, semi-educated vendors in Jerusalem speak Hebrew, Arabic, and English, and in Lebanon and Syria fluency in Arabic and French is common. Overall, however, it appears that Greek usage had become more prominent than Aramaic.

2. My Reasons

Let me turn now to state my particular reasons for the belief that Jesus spoke Greek, not only Aramaic. My expectation was that the sources for the Gospels were chiefly oral and that they were expressed in Aramaic. Jesus was the great teacher of orally memorised parables, poems, riddles and aphorisms—instructions that were delivered in the lingua franca, Aramaic, as I had supposed it to be. I had to overcome a strong intuition and prejudice that Jesus’ teachings were not recalled by the memory in the language of the people, Aramaic. The weight of evidence, however, I believe points in another direction.

First, there is the issue of chronology. Something immediately to resolve is the length of the lead-time between Jesus of Nazareth and the earliest written Gospel. A span of many generations would weaken confidence about the accuracy of the record. Mark, however, wrote his Gospel—the earliest of the four—about only thirty years after Jesus, which is the span of one generation.8Based on modern and western life expectancy, a generation is 25–30 years.

The letters of Paul, James and Peter (i.e. 1 Peter), which were written between the time of Jesus and the Gospel of Mark, are windows enabling us to see the development of Christianity within the period between Jesus and the first written Gospel.

| AD 29–33 | The public ministry of Jesus |

| AD 33–42 | Peter’s leadership of the Church in Israel |

| AD 33–62 | James’s membership of and subsequent leadership of the Church in Israel |

| AD 55–64 (?) | Peter’s leadership of the Church in Rome |

| AD 64/65 | Practical completion of the Gospel of Mark |

From the apostles’ letters and the book of Acts, there was constant gospel activity in the relatively few years between Jesus and the writing of the Gospels. By contrast, it was more than 80 years after Tiberius Caesar’s death that Suetonius wrote his Life of Tiberius. So far as is known, those eight decades were ‘dead’ years, with the absence of a cult following for the deceased emperor. Tiberius was not well remembered.

The relatively few years between Jesus and the earliest written gospel text means an effective time constraint against the possibility of radically refashioning the traditions to obliterate Jesus as he was, to replace him as, for example, a Greek miracle-working redeemer-god who died and rose again.

Of critical importance is the observation that the letters of Paul, James, and Peter contain echoes of the sources of the tradition that would appear within the Gospel of Mark, but also of Matthew and Luke. It was the examination of the sources (early) Mark (echoed in Romans mainly), ‘Q’, ‘L’, and ‘M’, as found in the letters of Paul, James, and (First) Peter that attracted my attention. The dating of these letters is important. They were written between (approximately) AD 48–64, which means that the words they quote or echo must have been established beforehand.

The critical thing is that these sources are cited in the apostolic letters in Greek. Furthermore, these Greek citations in the letters do not back translate into Aramaic. Counter-intuitive though it is, I think we must push back closer to Jesus and conclude that these text sources began to be written in Greek from or soon after the post-Easter period.

In support of this viewpoint, I point to the relatively infrequent examples of surviving Aramaic in Paul’s letters, the earliest texts in early Christianity. Surprisingly, few words of Aramaic find their way into his letters.

| Abba | Gal 4:6; Rom 8:15 |

| Maran atha | 1 Cor 16:22 |

| Amēn | 2 Cor 1:20 |

If the deposit of Jesus’ teachings and the record of his deeds was transmitted in Aramaic, considerable echoes of Aramaic in the letters of Paul, James, and Peter would be expected. However, there are few such echoes.

By contrast, the early pre-formatted traditions Paul repeats in 1 Corinthians—the Last Supper tradition and the Easter tradition—are in Greek (11:23–25; 15:3–7). Some scholars claim to have found traces of the original Aramaic in these texts, but the stubborn reality is that they survive in 1 Corinthians in Greek.

Regarding Aramaic, there is the occurrence of that language mainly in the Gospel of Mark but also in the ‘Q’ source.9See Millard, Reading and Writing, 140–141; J. Jeremias, New Testament Theology 1 (London: SCM, 1971), 3–8. Embedded within these Greek texts are Aramaic place names (e.g. Akeldama, Bethzatha, Gabbatha, Golgotha), Aramaic surnames (e.g. Cephas, Boanerges), words in common usage (e.g. korban, messias, cananaean, hosanna, pascha, rabbi, satanas), words spoken by Jesus (e.g. amēn, mammōn, raka, talitha cumi, ephthatha, abba, Eloi Eloi lema sabachthani). Surely, these point to the Gospel of Mark and ‘Q’ having been written in Aramaic. Still, that Gospel and that source resist the efforts to back translate them into Aramaic, even though its authors confidently use Aramaic words.

Meyers and Strange refer to the growing Greek usage in Israel:

Aramaic, at first the language of all the people, gradually suffered a decline that probably accelerated with each war against Rome. It appears that sometime during the first century b.c.e. Aramaic and Greek changed places as Greek spread into the countryside and as Aramaic declined among the educated and among urban dwellers.10Eric M. Meyers and James F. Strange, Archaeology, the Rabbis and Early Christianity (London: SCM, 1981), 90; Stanley E. Porter, ‘Jesus and the Use of Greek: A Response to Maurice Casey’, Bulletin of Biblical Research 10, no. 1 (2000), 71–87. Historically, the majority of scholars (e.g. Wellhausen, Joüon, Bardy, Black, Wilcox, Feldman, Torrey, Fitzmyer) supported Dalman’s conclusion that though Jesus might have known Hebrew and probably spoke Greek, he certainly taught in Aramaic. See Randall Buth and R. Steven Notley (eds), The Language Environment of First Century Judaea. Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels—Volume Two (Leiden: Brill, 2014), for articles debating the relative use of Aramaic and Hebrew in Palestine in the era of the New Testament.

Judea, as a now-entrenched Roman province, attracted Greek-speaking soldiers, bureaucrats and traders who promoted the spread of Greek.11Porter, ‘Jesus and the use of Greek’, 71–87.

To state the obvious, since Jesus is quoted in Greek and Aramaic in the Gospel of Mark, it is reasonable to conclude that Jesus taught in both languages. Recent studies such as that by Porter no longer limit probable conversations in Greek to Jesus meeting in private with the Syro-Phoenician woman, the centurion in Capernaum, or Pilate.12As argued, for example, by Stanley E. Porter, ‘Did Jesus Ever Teach in Greek?’ Tyndale Bulletin 44 (1993), 199–235. Many now accept that Jesus also taught publicly in Greek.

Since Jesus is quoted in Greek and Aramaic in the Gospel of Mark, it is reasonable to conclude that Jesus taught in both languages

Large crowds from Greek-speaking regions—‘all over Syria’ (Matt 4:24), ‘the Decapolis’ (Matt 4:25), and ‘the coastal region around Tyre and Sidon’ (Luke 6:17)—came to hear Jesus teach. They would not have made that journey unless they knew Jesus would be speaking their language, Greek.

It can readily be imagined that Jesus taught in both languages when attended by large crowds. Jesus would have ensured that both language groups understood his message. Those who understood in both languages would have the additional benefit of memory enhanced by repetition.

Accordingly, the task of translating Jesus’ words from Aramaic to Greek did not happen initially in the years after the first Easter—even as early as by the ‘Hellenists’ in the Jerusalem church.13So Martin Hengel, ‘Eye-witness Memory and the Writing of the Gospels: Form Criticism, Community Tradition and the Authority of the Authors’, The Written Gospel, eds. Markus Bockmuehl and Donald A. Hagner (Cambridge: CUP, 2005), 70–96 (at 83). Jesus himself had already done this in the course of his public teaching.

3. Recording the Words of Jesus

The popular view that Jesus’ followers were illiterate artisans has rightly been discarded.14So, for example, D. A. Fiensy, ‘Jesus’ Socioeconomic Background’, Hillel and Jesus: Comparisons of Two Major Religious Leaders, eds James H. Charlesworth and Loren L. Johns (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1997), 224–255; Sean Freyne, Galilee, Jesus and the Gospels: Literary Approaches and Historical Investigations (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1988), 241; Craig S. Keener, The Historical Jesus of the Gospels (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2009), 20–21, 182–184; Ben Witherington III, The Jesus Quest: The Third Search for the Jew of Nazareth, 2nd edn (Downers Grove: IVP, 1997), 82–86, 239–241. The four fishermen (Simon, Andrew, James and John) ran a business cooperative. Several at least among his disciples were both literate and numerate—for example, the customs collector, Matthew.

Furthermore, archaeological discoveries have opened a window for our understanding of the creation of written records.15See especially Millard, Reading and Writing, 154–184. It can well be envisaged that the narratives of ‘the things that have been fulfilled among us’ (Luke 1:1) were written post-Easter. This process, however, may well have begun during the brief pre-Easter years.16Building on the 1961 essay of Hans Schürmann, a 1975 essay by E. Earle Ellis argued that such records were produced during Jesus’ ministry: ‘New Directions in Form Criticism’, published again in Prophecy and Hermeneutic in Early Christianity (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1978), 237–253 (at 240–247). See also Richard Bauckham, Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony, 2nd edn (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017), 287–289; E. Earle Ellis, The Making of the New Testament Documents (Leiden: Brill, 2002), 22, 32; Birger Gerhardsson, The Reliability of the Gospel Tradition (Peabody: Hendrickson, 2001), 11–13, 85; Craig S. Keener, ‘Assumptions in Historical-Jesus Research: Using Ancient Biographies and Disciples’ Traditioning as Control’, JSHJ 9, no. 1 (2011), 26–58 (at 45–48); Millard, Reading and Writing, 185–229.

The Gospels were written in Greek; the sources underlying Matthew and Luke were written in Greek; echoes of these sources in the letters of Paul, James, and Peter were most probably written in Greek. The most logical conclusion is that the sources of the Gospels were also written in Greek from their beginnings, based on the likelihood that Jesus often taught in Greek (as well as Aramaic). Jesus’ words and deeds were committed to writing in Greek from earliest times. It is believed that this process began during those few years Jesus was active in his messianic ministry, accompanied as he was by the twelve disciples (apprentices).

The consequence of this is significant and controversial. Aramaic-based oral transmission played only a temporary role in early Christianity. If this explanation is correct, it means that the elaborate theories of oral transmission developed by Kenneth Bailey and followed by James Dunn,17James D. G. Dunn, Jesus Remembered (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 205–210, referring to Kenneth Bailey, ‘Informal Controlled Oral Tradition and the Synoptic Gospels’, Asia Journal of Theology 5 (1991), 34–54. for example, need to be reconsidered. Jesus delivered his message of the kingdom in both Aramaic and Greek, and from the beginning it may have been written in both. However, the case is strong that the message was soon written in Greek.

4. A Brief Lead-time

As stated, the brevity factor should be recognised. Because the letters of Paul that echo many of Jesus’ words can be dated (especially 1 Corinthians in AD 55 and Romans in 56), the practical limits by which Paul had access to these source traditions can be set.

The lead-time of thirty or so years between Jesus and the writing of Mark’s Gospel can be plotted. This is a brief and limited period—certainly not the timespan in which a radical refashioning of Jesus would have occurred. The deviating, Gnostic re-portrayals of Jesus occurred in the second century. Valentinus, for example, wrote his Gospel of Truth more than a century after Jesus.

5. Conclusion

This paper has offered suggestions about the languages of first century Palestine and the languages in which Jesus taught. Widely held are the views that the Aramaic was the principal language, that Jesus conversed in Aramaic, and that his teaching was remembered in Aramaic.

The evidence, however, points to the currency of both Aramaic and Greek, but with the latter gaining the ascendancy. This, it is argued, is reflected in Jesus use of both, but with his greater use of Greek. From the beginning, therefore, Greek became the vehicle for the new faith, including in the creation of the sources that would evolve into the text of the four Gospels.

As to the mode of transmission, there is a better argument for transmission by individual eyewitnesses than for some form of community-based storytelling. Oral transmission doubtless had a role, but it was secondary and diminished with the passing of the years.

Afterword: Josephus and ‘the language of our country’

Josephus initially wrote the Jewish War ‘in the language of our country’, Aramaic, and sent it to people of ‘Parthia, Babylonia, and Arabia and the Jewish Dispersion in Mesopotamia and the inhabitants of Adiabene’ (Jewish War 1.6). In Rome, Josephus determined to translate the Jewish War into the Greek tongue ‘for the sake of such as live under the government of the Romans’ (Jewish War 1.3).

Josephus made these comments regarding Greek:

I have also taken a great deal of pains to obtain the learning of the Greek, and understand the elements of the Greek language, although I have so long accustomed myself to speak our own tongue, that I cannot pronounce Greek with sufficient exactness… (Jewish Antiquities 20.11)

Josephus refers to Aramaic as ‘our own tongue.’

This is how Josephus worked on the rewritten Greek version of the Jewish War:

Then, in the leisure that Rome afforded me, with all my materials in readiness, and with the aid of some assistants for the Greek, at last I committed to writing my narrative of the events. (Against Apion 1.50)

Josephus may be understood to be saying that Greek was unknown to him and that Aramaic was ‘our own tongue’ and ‘the language of our country’.

Is it possible, however, that his background as an aristocrat and a Pharisee cloistered him in an Aramaic-speaking world, so that he was not schooled in writing Greek? The vast expanses of Greek in Antiquities, War, Apion, and Life make it difficult to believe that Josephus had to learn to write Greek de novo. The quality of the Greek of these extensive texts does not reflect the labours of a late learner. It is more likely that Josephus had at least a rudimentary knowledge of spoken Greek before his ‘assistants’ supported him through the writing of the Jewish War. It appears that Jewish War is thoroughly Greek and reflects no dependence on an Aramaic original, but is an independent, re-written work that does not translate his Aramaic original.