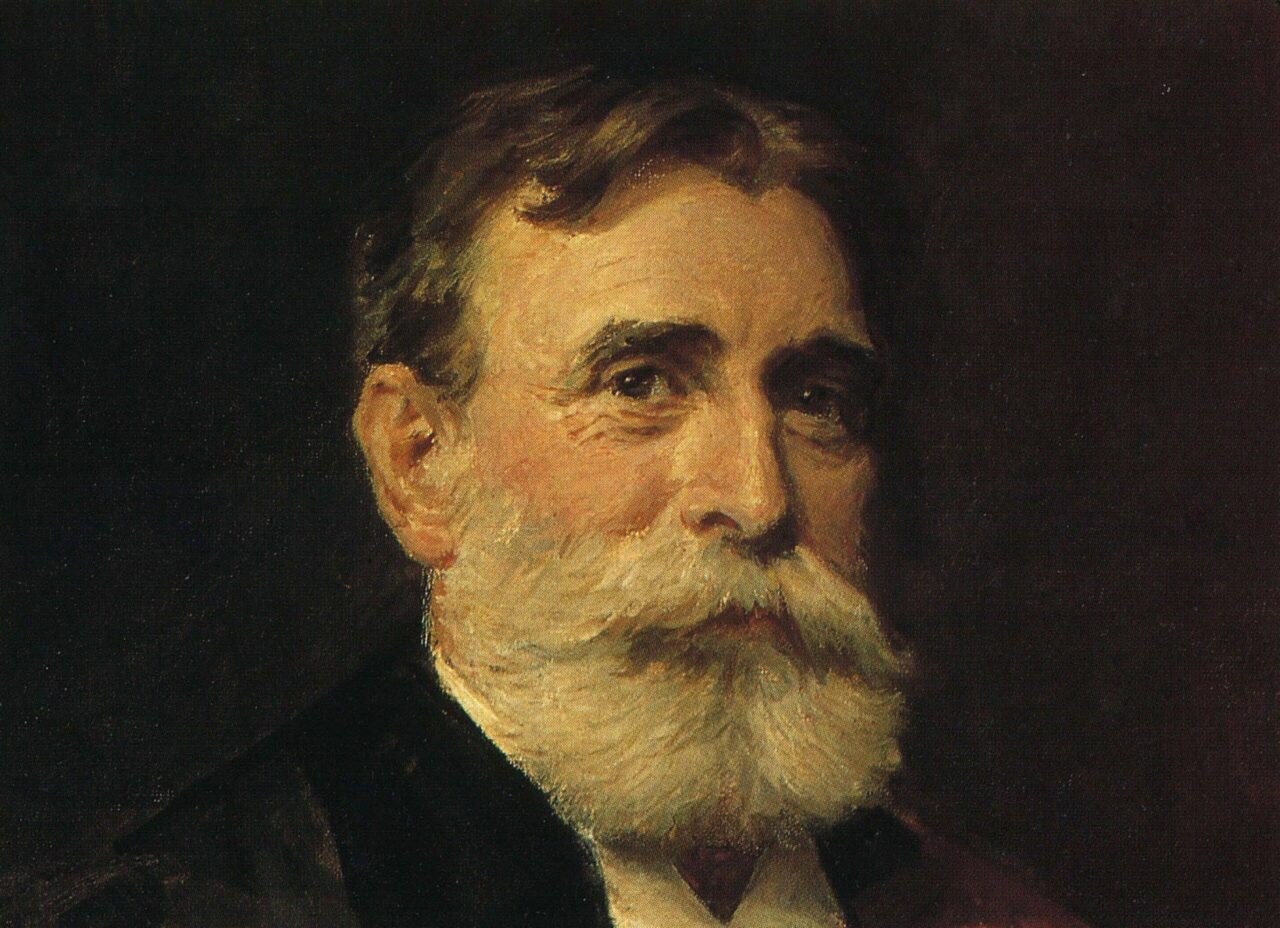

In a previous article, I began exploring the extent to which B. B. Warfield’s (and A. A. Hodge’s) doctrine of inerrancy corresponds with the doctrine of Scripture in the Westminster Confession of Faith. That article covered the easy part and concluded that Warfield and the Confession both teach the entire truthfulness of Scripture. Warfield even favoured using one of the terms that the Confession uses to express the entire truthfulness of Scripture, namely ‘infallibility’, rather than using the word for which he is better known, ‘inerrancy’.

The second step is slightly harder (and a third step not taken now is even more contentious). Warfield’s doctrine of inerrancy added a qualification. Scripture’s entire truthfulness properly belonged to the ancient texts authored by the apostles and prophets. These are the so-called ‘autographs’ or autographa. Inerrancy did not properly belong to the manuscripts available today—the extant Greek and Hebrew copies, sometimes called the ‘apographs’ or apograph (noting that the discussion is not about English or other translations).

The problem is that some claim that the Westminster Confession and indeed the Reformed tradition has little interest in the autographs. The Confession apparently speaks only of the truth of the faithful, original-language copies of Scripture. If you pick up a Hebrew Old Testament or a Greek New Testament, you are picking up an infallible text, as it were (with a few provisos). Richard Muller has a profound understanding of Reformation-era theology, and his stinging critique of inerrancy is thus:

It is important to note that the Reformed orthodox insistence on the identification of the Hebrew and Greek texts as alone authentic does not demand direct reference to autograph in those languages; the ‘original and authentic text’ of Scripture means, beyond the autograph copies, the legitimate tradition of Hebrew and Greek apograph…The case for Scripture as an infallible rule of faith and practice and the separate arguments for a received text free from major (i.e., non-scribal) errors rests on an examination of apographa and does not seek the infinite regress of the lost autographa as a prop for textual infallibility.1Richard A. Muller, Post Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2: Holy Scripture (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 1993), 413–414.

Was Warfield’s emphasis on the autographs novel in the Reformed tradition? First, two wrong understandings of Warfield’s view of both the autographa and apographa will be reviewed. Secondly, the Confession’s view of the autographs will be laid out and correlated with Warfield’s reason for stressing the autographa.

Contents

1. Warfield: avoiding or embracing rationalism?

1.1 Avoiding rationalism with the autographa?

There is something of an urban legend to the effect that Warfield’s emphasis on the autographs was an attempt to safeguard the Bible from the attacks of the biblical higher critics (the ‘liberals’, as we might call them). What happens if a fault or untruth is found in the copies today, and our doctrine of Scripture stresses the copies? The Bible is falsified. However, the autographs are not extant, so they cannot be criticised and proved wrong. Any errors in the extant copies can be passed off as faults in scribal transmission. Someone made a mistake when copying out the Greek or Hebrew.

Warfield and Hodge would thus be setting a logical trap or a conundrum designed to confound the critics. Genuine errancy can never be proved because the autographs are beyond reach. As Muller puts it, the appeal to the autographs is a ‘prop’ for infallibility.

Warfield did not appeal to the autographs to solve allegations of error in Scripture.

It is a remarkable urban legend. How crafty Hodge and Warfield were. The problem is that it does not match reality. Hodge and Warfield repeatedly invited critics to present evidence of errors in the extant manuscripts. They wanted to sort through allegations of fault and demonstrate that there was no error. No one has yet shown that Warfield appealed to the autographs to solve an allegation of error in Scripture.2Raymond D. Cannata, ‘Warfield and Doctrine of Scripture’, B. B. Warfield: Essays on His Life and Thought, ed. Gary L. W. Johnson (Phillipsburg: P&R, 2007), 101. He did not make that argument.

This indicates that Warfield saw a very high level of continuity between the autographs and the extant copies, to the extent that the copies were treated in effect as infallible. The ancient manuscripts may be long gone, but their text could still be accessed in the copies and so tested.

1.2 Embracing rationalism with the apographa?

The irony is that some complain that Hodge and Warfield are too scientific and too willing to prove that the Bible is true. This stresses the apographa! They are rationalists. They based too much of their faith upon human reason. This is the more typical criticism of Hodge and Warfield and the entire old Princeton school.3Andrew T. B. McGowan, The Divine Spiration of Scripture: Challenging Evangelical Perspectives (Nottingham: Apollos, 2007), 114–115; Jack B. Rogers and Donald K. McKim, The Authority and Interpretation of the Bible: An Historical Approach (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), 330; Ernest R. Sandeen, The Roots of Fundamentalism: British and American Millenarianism, 1800–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1970), 118–121. For responses, see Michael D. Williams, ‘The Church, A Pillar of Truth: B. B. Warfield’s Church Doctrine of Inspiration’, Did God Really Say? Affirming the Truthfulness and Trustworthiness of Scripture, ed. David B. Garner (Phillipsburg: P&R, 2012), 24–25, and the references provided there. See also Paul Helm, ‘B. B. Warfield’s Path to Inerrancy: An Attempt to Correct Some Serious Misunderstandings’, WTJ 72, no. 1 (2010), 25–26.

Some still lay this complaint against inerrantists today. They always want to prove the Bible. They are not happy simply believing that the Bible is true. They need archaeology, scientific data, and logic and argumentation to clear the Bible of errors and give their faith a firm foundation. What happens, though, when the latest archaeological discovery seems to contradict the apparently certain facts? Do we lose our faith? This is a shaky foundation, then.

Hodge and Warfield were not seeking to rationalise the faith. They did give some arguments that demonstrate that some alleged errors were not errors at all. However, they did not go through long lists of alleged faults. They sought to demonstrate consistency with reason, not to give absolute proof of Scripture’s truth.

‘Inerrancy’ seeks to encourage non-Christians not to dismiss the Bible out of hand.

Their interest was apologetical. ‘Inerrancy’ seeks to encourage non-Christians not to dismiss the Bible out of hand (see further below). Their interest was also pastoral, seeking to assure God’s people that faith is reasonable. This is why Warfield and Hodge’s watershed 1881 article, ‘Infallibility’, concludes by saying that when ‘objections’ have been ‘rebutted’, ‘faith’ moves to ‘rational conviction’. It is faith seeking understanding, not vice versa. Infallibility ‘rests primarily on the claims of the sacred writers’. In other words, we believe in infallibility because the Bible teaches infallibility.

Hodge and Warfield were probably a bit more excited by external or scientific and archaeological verification of Scripture than others might be. Still, they are correct that some truth claims in the Bible can be verified. That does have to be faced.

The idea of rational confirmation is not out of step with the Reformed tradition. The Westminster Confession itself says that Scripture ‘doth abundantly evidence itself to be the Word of God’ (1.5). A long list of rational evidences is given. Still, like Warfield, the Confession does not base faith on evidence, but rather WCF 1.5 turns to the Spirit’s ministry.

The apographa have a significant place in Warfield’s thought. As to the primary reason he still turned to the autographa, that will be better understood once the Confession’s outlook is appreciated, which is the next point.

2. Are the Autographs Mentioned in the Confession?

Did Hodge and Warfield give a higher place to the ancient apostolic and prophetic autographs than is usually found in the Reformed tradition? What does the Confession say about the autographs? Confession 1.8 says:

The Old Testament in Hebrew (which was the native language of the people of God of old), and the New Testament in Greek (which, at the time of the writing of it, was most generally known to the nations), being immediately inspired by God, and, by His singular care and providence, kept pure in all ages, are therefore authentical; so as, in all controversies of religion, the Church is finally to appeal unto them.

There seems to be no ‘direct reference’ to the autographa in 1.8, or such seems not to be explicitly ‘demanded’ (citing Muller’s comments again about the Reformed tradition). However, the autographa are present in four ways.

2.1 ‘At the time of writing’

WCF 1.8 might focus on the apographa, but the divines clearly speak of the apostolic texts, albeit in parenthesis. The New Testament, ‘at the time of the writing of it’, was written in Greek. In the standard language used in 17th-century theology, this refers to the autographa.

In making what was an obvious observation that only needed a short paragraph to state, it begins to feel like a surreal discussion. How can copies be in view without some view of that which is copied, whether stated or otherwise? Does one see where a river terminates and have no concept that it must have a place of origin? How likely is it that the Reformed orthodox, who carefully differentiated the apographa and autographa, did not also carefully correlate the two?

2.2 ‘Kept pure’

The Confession says that the extant texts have been ‘kept pure’ (1.8). As to what ‘pure’ means, the same expression, ‘kept pure’, occurs in a different context but still in an enlightening way in 23.3. It is the duty of the civil magistrate ‘to take order that unity and peace be preserved in the Church, that the truth of God be kept pure and entire’. Pure in an adjective of truth.

The divines can stress the purity of the copies only for this reason: because of an easy assumption of the original purity of the autographs. This is not a ‘direct’ reference to the purity of the autographa, but surely the word ‘kept’ cannot be ignored, either. It carries a clear implication. That which is now is because of that which was.

The Confession did not stress the purity of the autographa because it was not a point of controversy.

One can say that there is no emphasis placed on the purity of the autographs in the Confession, and that might formally be true, yet the reason that there is no such emphasis is its own form of emphasis. The Confession did not stress the purity of the autographa because it was not a point of controversy. There was debate about the purity of the copies, primarily because the Roman Church had found that the extant original-language texts threatened its authority. It was far better, the Roman Church believed, to stay with the Latin Vulgate. Regarding the autographa, though, there was no dispute. It is inappropriate to turn ‘no dispute’ into ‘no reference’.

2.3 ‘Immediately inspired’

The divines spoke explicitly of a unique attribute or reality that belongs only to the autographa. The ‘Hebrew’ and ‘Greek’ autographa are ‘immediately inspired by God’ (with the Confession not following the Geneva or King James Bibles: ‘given by inspiration of God’). The sentence is syntactically clumsy, and if followed strictly, it would seem to say that both the autographs and the copies are immediately inspired. However, there is no reason to believe that the term ‘immediately inspired’ was meant of the copies. What would that mean—that every copy was inspired when transcribed; a doctrine of ongoing inspiration? The apographa bear the effects of inspiration, but the act of inspiration does not ‘immediately’ take place in the copying.

As Francis Turretin (1623–1687) put it, the apographs ‘are so called because they set forth to us the word of God in the very words of those who wrote under the immediate inspiration of the Holy Spirit.’4Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, vol. 1, ed. James T. Dennison Jr., trans. George Musgrave Giger (Phillipsburg: P&R, 1992–1997), 106. Inspiration belongs to the autographs. Turretin was clear about the nature of the autographa and used similar language to the Confession, so far is it from this being a strange idea in the Reformed tradition.

The Confession attributes more than ‘purity’ to the autographs. The autographs were inspired.

The Westminster divines do not explicitly say that the autographs are where the initial purity is located. They attribute more than that to the autographs. The autographs were inspired. The copies are of a lesser status in the Confession, for they are not inspired. They share an implication of the immediate inspiration, which is purity. The Westminster divines have moved from the greater to the lesser truth or from the cause to one of the most important effects. In other words, the autographa are essential for the infallibility of the apographa. Since there was inspiration, there is purity.

2.4 ‘Authentical’

A fourth term in 1.8 could imply the autographa, namely ‘authentical’. The Confession does not explain the term. It comes from the Greek word, authentikos, which means ‘genuine’. If an object is authentic, its claimed origins are its true origins. An ‘authentic Stradivarius’ means that the famous luthier indeed crafted the instrument. ‘Authentical’ requires a source; hence, authentical apographa require the autographa.

2.4 Correlation with Warfield

Warfield was thoroughly familiar with the Confession’s teaching on the autographs. First, he writes, ‘how seriously erroneous it is to say…that the Westminster divines never “thought of the original manuscripts of the Bible as distinct from the copies in their possession.” They could not help thinking of them.’5B. B. Warfield, ‘The Inerrancy of the Original Autographs’, Selected Shorter Writings of Benjamin Warfield, vol. 2, ed. John E. Meeter (Nutley, NJ: P&R, 1973 [1893]), 586.

Secondly, he directly discusses what ‘authentical’ means. It means that the extant Greek and Hebrew texts are ‘genuine’ and and authoritative.6Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield, ‘Inspiration and Criticism’, Revelation and Inspiration (New York: OUP, 1927), 408–410. That can only mean that providential oversight of the process of transmission means that the apographa contain the inspired words of God found in the autographa.

Most importantly, the flow of the logic in the Confession is vital and correlates with Warfield’s main argument. The Confession moves from ‘immediately inspired’ to ‘kept pure’. That logic should look familiar because Hodge and Warfield follow this in inverse order. The stress of their article, ‘Inspiration’, is that testing the apographa for purity demonstrates the inspiration of the autographa (where the original purity is to be found). This is the logic of the Confession harnessed for apologetical purposes.

To reiterate, the correlative flow of logic is thus:

WCF: Inspired autographs > Pure apographs > Evidences

Warfield: Evidences > Pure apographs > Inspired autographs

This does not fully explain why Warfield chose to emphasise infallibility in the autographa rather than the apographs, but it would be a long bow to draw to say that the Confession does not give the autographs a special place or does not open the door to Warfield’s view.

3. Conclusion

Hodge and Warfield’s emphasis on the autographs is distinct from the Confession by way of clarity but not by substantial divergence. They state at length what the historical context allowed the Westminster divines to assume easily. The Confession has the inspiration of the autographa resulting in the purity in the apographa, and it speaks of the evidences that Scripture is the Word of God. Warfield wants to evaluate the evidences to confirm the purity of the apographa, which will then demonstrate the inspiration of the autographa. He harnesses the logic of the Confession for apologetical purposes.

If the question is whether the Confession teaches inerrancy, the quick answer is in the affirmative. The Confession has the autographa in view and by no means allows for error in them.

So that the importance of the overarching topic is not lost in the minutiae, it should be remembered that the autographs of Scripture are not a curiosity for academic debate. The texts written by the apostles and prophets are a great miracle, breathed out by God. These words, which have been handed down to us, are ‘pure, like silver… purified seven times’ (Ps 12:6). Our response is not to critique but to approach with wonder, to embrace with washed hands, and to find in them by the ministry of the Spirit our Saviour and our God.