First published: Peter Barnes, ‘The Free Offer of the Gospel’, The Reformed Theological Review 59, no. 1 (April 2000), 28–36.

Rabbi Duncan is well-known for his aphorism: ‘Hyper-Calvinism is all house and no door; Arminianism is all door and no house.’ However, the issue is not just about Calvinism, Hyper-Calvinism, and Arminianism, for there are themes and variations. Ken Stebbins cites Robert Lewis Dabney: ‘any man who can contribute his mite to a more satisfying and consistent exposition of the Scripture’s bearing on it [the divine will] is doing a good service to truth’.1K. Stebbins, Christ Freely Offered (Strathpine North: Covenanter Press, 1978), p.7. In such a spirit, it is worth having another look at the free offer of the gospel. More specifically, does God lovingly and sincerely offer the gospel to the non-elect?

Contents

1. The History of the Free Offer

Down through the centuries, the issue of the free offer of the gospel has raised its head a number of times, both directly and indirectly. As is well- known in 1619 the Synod of Dordt came up with the so-called five points of Calvinism in response to Arminianism. These are: T (Total Depravity); U (Unconditional Election); L (Limited or Definite Atonement); I (Irresistible Grace); P (Perseverance of the Saints). Then came Amyraldianism, or four point Calvinism. John Cameron and Moise Amyraut (1596-1664) both claimed that Beza distorted Calvin, and held to a hypothetical universalism. In this scheme, the Father predestines His elect, but Christ died for all the world. Amyraut’s views were accepted, with some variations, by John Davenant at Dordt, and by Arrowsmith, Sprigge, Pritte, Carlyle, Burroughs, Strong, Seaman and Calumy at the Westminster Assembly. In the inflated language of Herman Hanko, Amyraldianism ‘destroys all the truth of the gospel’.2H. Hanko, The History of the Free Offer (Michigan: Protestant Reformed Churches, 1989), p.221.

In early eighteenth century Scotland the Marrow Controversy broke out.3H. Hanko, The History of the Free Offer (Michigan: Protestant Reformed Churches, 1989), p.221. In 1717 the Auchterarder Presbytery examined a student named William Craig for licence, and asked him to subscribe to the following statement: ‘I believe that it is not sound and orthodox to teach that we must forsake sin in order to our coming to Christ, and instating us in covenant with God. ’ Craig refused to sign this ambiguous creed,4It was meant to block any legalistic preparationism, but it could easily be read in an antinomian sense. Boston was being rather charitable in calling it ‘truth, howbeit not well worded’. See Thomas Boston, Memoirs (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1988), p.317. and appealed to the General Assembly, which supported him. This led on to the Assembly’s condemnation of the anonymous Marrow of Modern Divinity in 1720, and again in 1722, despite the support the work received from Thomas Boston and Ralph and Ebenezer Erskine. The Marrow declares: ‘Go and tell every man without exception that here is good news for him; Christ is dead for him, and if he will take Him and accept His righteousness he shall have Him.’

The Marrow declares: ‘Go and tell every man without exception that here is good news for him; Christ is dead for him, and if he will take Him and accept His righteousness he shall have Him.’

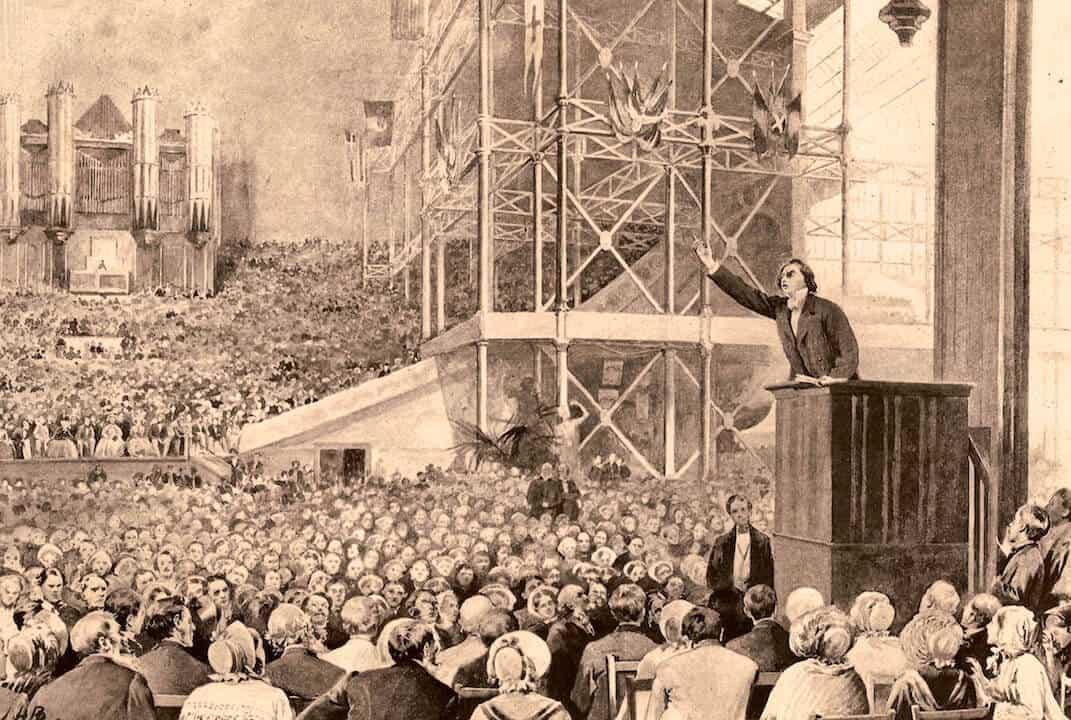

The English Baptists of the eighteenth century also veered towards Hyper-Calvinism. It was Andrew Fuller’s book, The Gospel Worthy of All Acceptation, which helped William Carey to see that Hyper-Calvinism is contrary to Scripture. In 1793, he sailed for India, and was to labour there for the remaining 41 years of his life. In the next century, in 1855, England’s most renowned Baptist, Charles Spurgeon, not only had doctrinal battles over baptismal regeneration, Arminianism and liberalism, but also against Hyper- Calvinism.5See Iain Murray, Spurgeon v. Hyper-Calvinism: The Battle for Gospel Preaching (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1995).

For our purposes, it is best to concentrate on some of the issues raised by the formation of the Protestant Reformed Churches in 1924 in the United States. That was the year in which the Christian Reformed Churches accepted three points of common grace. The ensuing controversy led to Herman Hoeksema’s deposition from office and the formation of the Protestant Reformed Churches. The Protestant Reformed Churches (PRC) repudiate common grace, general revelation, and any well-meant offer of God to the non-elect.

2. The Issues

Four issues will be looked at, but it is the fourth one that will be examined at greater length.

1. Are the gospel invitations universal?

It is surely clear that Scripture’s gospel invitations are delivered to all and sundry. This is shown from the following passages: Isaiah 55:1-3; Matthew 11:28; 22:14; 28:19-20; Acts 17:30; Revelation 22:17. The Synod of Dordt says that God ‘unfeignedly’ calls everyone. It affirms: ‘The command to repent and believe ought to be declared and published to all nations and to all persons promiscuously and without distinction, to whom God out of his good pleasure sends the gospel. ’ To deny this is fall into Hyper-Calvinism

2. Are we commanded to believe?

Hyper-Calvinists such as Lewis Wayman (d.1764), John Brine (1703-65) and John Gill (1697-1771) denied that the reprobate unbeliever is required by God to believe in Christ. The Gospel Standard (Baptist) Churches in England deny ‘duty faith and duty repentance’, fearing that it may encourage a belief in ‘creature power’. But clearly God commands all to repent and believe. We are even told to choose! (Deut. 30:15-19; Josh. 24:14-15). As Paul told the Athenians, God ‘commands all men everywhere to repent’ (Acts 17:30).

3. Are we responsible for our actions?

Obviously the answer again is ‘Yes’. All of Scripture tells us that God holds us accountable for our actions. Even pagans without the Scriptures are still held accountable for their sins against the law of God written upon their hearts (see Amos l:3-2:3; Rom. 2:14-16).

4. Does God love all mankind?

This is the specific issue raised by the Protestant Reformed Churches in the USA, and by the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in Australia. Herman Hoekema says that the offer goes to all but God has no loving intention to all. Francis Turretin wrote: ‘Now to say that God intended salvation for all and at the same time decreed to elect and love some, but to hate and reprobate others, is most absurd.’6Cited in D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism and the Call of the Gospel, (Michigan: Reformed Free Publishing Association Churches, 1994), p. 155. To suggest any turmoil in the heart of God was, in Turretin’s view, to make His goodness and grace ‘vain and inefficacious’ and ‘repugnant to his wisdom and power’.7D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.155.

The Protestant Reformed Churches repudiate Hyper-Calvinism but they are fearful of any frustration in God’s desires. J. H. Gerstner (who was not a member of the PRC) wrote: ‘God, if He could be frustrated in His desires, simply would not be God.’8D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.6. Hoeksema wrote of ‘double-track theology’ and of the ‘Janus head’ of churches who taught election and a common love to all.

Abraham Kuyper thought the idea of two wills in God was ‘gibberish’. Engelsma says that if God reprobates those whom He loves, He would become guilty of ‘insincere deceptive behavior’.9D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism,.., p.164.

In reply to this, Ken Stebbins rightly says that God can love sovereignly whom He hates judicially.10K. Stebbins, Christ Freely Offered, p.61. God loves and hates the elect before they were Christians. The elect were once, like the others, ‘children of wrath’ but at the same time under God’s great love with which He loved us. Such a love, of course, does not begin with the sinner’s conversion, but is from everlasting to everlasting (see Eph. 1:3,4). Before a sinner repents and believes in Christ, the wrath of God is on him; for the unbeliever it abides on him (John 3:36).

Even after a person becomes a believer, it is possible to speak of God’s anger and hot displeasure against him/her (Ps. 6:1; 30:43; 38:1). Death as the universal human condition is a result of God’s anger against sinners, whether elect or reprobate (Ps. 90:7). God’s hatred is, of course, not malevolent and without cause but holy and with cause.

3. Common Grace

Abraham Kuyper wrote a three-volume work on common grace, but he opposed the well-meant offer. Engelsma, Hanko, and the Protestant Reformed Churches want ‘the complete repudiation of Kuyperian common grace.’11D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.178. Some kind of common grace is surely taught in Psalm 145:9; Matthew 5:44- 45; Luke 6:35-36; Acts 14:16-17. The reason why a Christian is to love his enemies is that God Himself shows concern for the welfare of His enemies. The Australian C. J. Connors desperately tries to avoid the implications of the verses in Matthew and Luke when he says that man’s duty to love all is one thing but God’s purpose and attitude may be another!12C. J. Connors, The Biblical Offer of the Gospel (Tasmania: Evangelical Presbyterian Church, 1996), p.50. We are to be perfect, even as our Father in heaven is perfect (Matt. 5:48) – i.e. our duty is definitely related to God’s character and attitude,

4. A Well-Meant Offer of Salvation?

Erroll Hulse took Kuyper the next step: ‘Common grace, then, finds its highest expression in that desire and will of God not only for fallen man’s temporal well-being, but for his soul’s salvation and eternal happiness.’13D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.177. Ken Stebbins tries to say that God has a ‘delight’ in the salvation of all, but not a ‘desire’.14K. Stebbins, Christ Freely Offered, p.20. Something like this is at work, although it is difficult to ground it in such a semantic distinction.

It is obviously nonsense to say that grace is offered equally to all. We are not all given an equal chance to believe in Christ. Yet John Murray and Ned Stonehouse affirm: ‘there is in God a benevolent lovingkindness towards the repentance and salvation of even those whom he has not decreed to save.’15Murray and Stonehouse, The Free Offer of the Gospel (OPC, 1948), p.27. John Murray asserts: ‘the universality of the demand for repentance implies a universal overture of grace.’16Murray, Collected Writings, vol 1 (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, 1976), p.60.

This, in David Engelsma’s view, has done ‘incalculable damage to the cause of Jesus Christ and the proclamation of His gospel.’17D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.ix. Engelsma considers that God’s call to all does not express His love for all nor does it imply that Jesus died for all. Rather, the call is ‘to render them inexcusable and to harden them’.18D. Engelsma, Hyper- Calvinism…, pp.24-5. Hoeksema said any well-meant offer was ‘terrible’ and ‘an enthronement of the will of man.’19D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.37. C. J. Connors writes: ‘The presentation of the gospel implies no active delight, desire or longing within God toward the salvation of all in the preaching.’20C. J. Connors, The Biblical Offer…, p. 11.

5. Some Texts

There are a number of pertinent texts which need to be examined order to tackle this question. Perhaps the obvious starting point is John 3:16. God loved the world, which Engelsma interprets to mean ‘the chosen out of the world’.21D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p. 156. A more likely interpretation is that both Jews and Gentiles are in mind, and God has a loving concern for the salvation of all.

1 Timothy 2:4 speaks of God’s desiring all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth. Given the context, with the reference to kings—even the maniacal Nero—Paul seems to saying that God’s saving purpose extends to all kinds of people.

However, it is difficult to apply 2 Peter 3:9 only to the elect, as Engelsma and Hanko do.22D. Engelsma, Hyper-Calvinism…, p.157; H. Hanko, The History…, p.237. God is not only longsuffering towards the elect. Indeed, Peter has just referred to Noah and the Flood where God waited 120 years before He fulfilled His threatened judgment on the world (Gen. 6:3). God is patient even with the reprobate.

Matthew 23:37 is Jesus’ lament over Jerusalem: Ό Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the one who kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to her! How often I wanted to gather your children together, as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing.’ Hanko asserts: ‘it is immediately evident that there is nothing even faintly resembling a well-meant offer of the gospel.’23H. Hanko, The History…, p.233. Surely it is obvious that there is. The blame for the punishment of Jerusalem is placed squarely on her sinful will. Jesus yearns for the salvation of those who refuse His gracious offer of salvation. Hanko goes on to claim that Jerusalem is not the people but ‘the city as the center of all Israel’s political and ecclesiastical life.’24H. Hanko, The History…, p.234. Such quibbling is hardly convincing.

In the book of Ezekiel, God declares that He has no pleasure in the death of the wicked (Ezek. 18:23,32; 33:11). Hanko says that God ‘has no pleasure in sin, but rather demands holiness of men.’25H. Hanko, The History…, p.231. This is true enough but the text refers to the fate of the wicked, not their behaviour. God has no pleasure in the fact that the wicked come to judgment, not just in the fact that the wicked sin. John Piper has written a work on The Pleasures of God which has the theme that ‘His [God’s] deeds are the overflow of his joy.’26J. Piper, The Pleasures of God (Oregon: Multnomah, 1991), p.50. Nevertheless, he is forced to acknowledge that God does not unequivocally delight in everything that He does.

Deuteronomy 28:63 does say that ‘the Lord will rejoice over you to destroy you and bring you to nothing’. When this is set next to the Ezekiel passages, John Piper can only conclude: ‘The answer I propose is that God is grieved in one sense by the death of the wicked, and pleased in another.’27J. Piper, The Pleasures of God, p.66.

There are a number of texts which emphasise that God has done all that is needed for the salvation of the sinner, and that the problem is located in the sinful will of human beings. In Isaiah 5:4, for example, God is said to have provided everything for His vineyard yet it is not saved. In the parable of the wedding feast all things were said to be ready (Matt. 22:4). The problem there is located in the will of those who were invited but who were not willing to come (Matt. 22:3) and in the fact that they were not chosen (Matt. 22:14). The two truths are left side by side in the parable.

Finally, in Mark 10:21 we read that Jesus loved the rich young ruler who walked away sorrowful from Him. Some expositors have felt awkward about this text, and New American Standard even says that Jesus ‘felt a love’ for the man-which is too weak, and not what the text says. Those who deny a well- meant offer of the gospel have sometimes resorted to the view that Jesus in His incarnation does not reflect the heart of God. This is precarious in the extreme. Jesus came to do His Father’s will (John 6:30, 38; Heb. 10:9). To see Jesus is to see the Father (John 14:9); Jesus is the complete embodiment of the Deity (Col. 2:9). If Jesus does not reflect the heart of God, we cannot know anything about the heart of God. Others have claimed that the rich young ruler was elect, but that is unproven and unprovable. We simply do not know and cannot know.

Spurgeon once complained about those who applied ‘grammatical gunpowder’ to texts, in order to deny their obvious meaning.28Cited in I. Murray, ״Spurgeon…, pp.150-1. We need to be careful. We must love God with our minds and be able to reason, but on this subject it is quite possible for analysis to lead to paralysis. Andrew Fuller had some wise words to say: ‘We shackle ourselves too much in our addresses to sinners; that we have bewildered and lost ourselves by taking the decrees of God as rules of action. Surely Peter and Paul never felt such scruples in their addresses as we do.’29Cited in A. F. P. Sell, The Great Debate, (Michigan: Baker, 1983), p.86.

6. Some Positive Conclusions

- There is a doctrine of reprobation. God declares that He will harden Pharaoh’s heart so that he would not let the Israelites go from Egypt (Ex. 4:21). Isaiah’s preaching would actually make the heart of his people dull, their ears heavy and their eyes shut, so that they could not return to God and be healed (Isa. 6:9-10). Paul affirms that God has mercy on whom He wills, and whom He wills, He hardens. God made one vessel for honour and another for dishonour, and wanted to show His wrath, power and longsuffering as well as His grace (Rom. 9:18, 21-23). The gospel is life to some, death to others (2 Cor. 2:14-16). The problem with the PRC view is not that there is no Scriptural doctrine of reprobation but that it maintains that that is the only way that God deals with the non-elect.

- God both hates and loves sinners. It is often said, even by someone as astute as Dr Martyn Lloyd-Jones, that ‘God hates the sin, but loves the sinner.’ There is much truth in this, but ultimately the sinner and his sin cannot be separated so easily. In any case, the Scripture says that God hates sinners (Ps. 5:5; 7:11; 11:5). It is not double-talk to say that God both loves and hates the same person, whether elect or non-elect.

- God can hardly expect us to be more merciful than He is. One of the lessons which Jonah had to learn was to be merciful as God is merciful (see Jonah 4). For all that, in evangelism we do not emphasise the love of God. The sermons in the book of Acts, whether to Jews or Gentiles, seek to make known first our accountability to God as our creator and judge, and then Jesus as the risen Lord and Christ (e.g. Acts 2:14-39 and 17:16-34). To tell an unbeliever that God loves him/her is not necessarily heretical, but it will be misunderstood by the unregenerate. Evangelism is for the sake of the elect (2 Tim. 2:10), but Paul prays for all and-amazing love-says he is prepared to be anathema for his fellow Jews (Rom. 9:1-3; 10:1). That is most moving, but it is only moving if it somehow reflects something of the mind and heart of God Himself.

- The God of the Bible is not Aristotle’s ‘unmoved mover’, but One who feels a tension between His mercy and justice. He does not inflict suffering willingly, or from the heart (Lam. 3:33). It is not something in which He takes delight. Indeed, His heart is churned up within Him at the thought of pouring out His anger on His sinful people (Hos. 11:8-9). There are a number of Oh passages in Scripture where God laments that Israel had not obeyed Him (see Deut. 5:29; 32:29; Ps. 81:13-14; Isa. 48:18). The PRC fear that this means that God’s will is ineffectual and frustrated is swept to one side. God is more concerned to reveal His loving desire for the salvation of sinners.

To tell an unbeliever that God loves him/her is not necessarily heretical, but it will be misunderstood by the unregenerate.

There are, in fact, a number of tensions e.g. God’s will and His decree in Bathsheba’s adultery and her bearing of Solomon. In telling Pharaoh to ‘Let My people go’, God is telling Pharaoh to do what He does not intend. Genesis 22 where God tells Abraham to sacrifice his son Isaac is an exception, and it is misleading for John Owen to say that God’s revealed will is not a reliable guide to what God delights in.30John Owen, Works, vol. 10 (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth, republished 1976), pp.44-45. Accusations of double-talk are a little out of place. All sides have to make some distinctions in the will of God, or in our perception of the will of God.

Dabney cites the example of George Washington’s reluctant execution of Major André, which is helpful. Nevertheless, as Stebbins points out: Washington could not meet the demands of justice; there are no motives behind God; and ultimately there are no unsatisfied longings in God.31Cited in K. Stebbins, Christ Freely Offered, pp.33-4.

On one occasion Charles Simeon was preaching on Romans 10:21 (All day long I have stretched forth my hands unto a disobedient and gainsaying people), when he was so overcome by the thought of God’s loving appeal to sinners that he burst into a flood of tears, and could not finish. If we do not know something of this, we ought not to be preaching. Even though God does love the non-elect, this will not be the starting point for presenting the gospel to them. Yet there has to be a wooing note, anchored in love to all. Richard Sibbes said that ‘The office of a minister is to be a wooer, to make up the marriage between Christ and Christian souls.’32Cited in I. Murray, Spurgeon…, p.54. Preaching is not just the proclamation of information. It is the proclaiming of God’s truth with the earnest desire that sinners be converted.