Part of the purpose of Catechesis is to give easier access to academic material that has been published elsewhere. I have just published an article on B. B. Warfield, comparing his view of inerrancy with the doctrine of infallibility in the Westminster Confession. This was in an issue of RTR acknowledging the anniversary of Warfield’s death. I am pleased to rework the article for Catechesis.

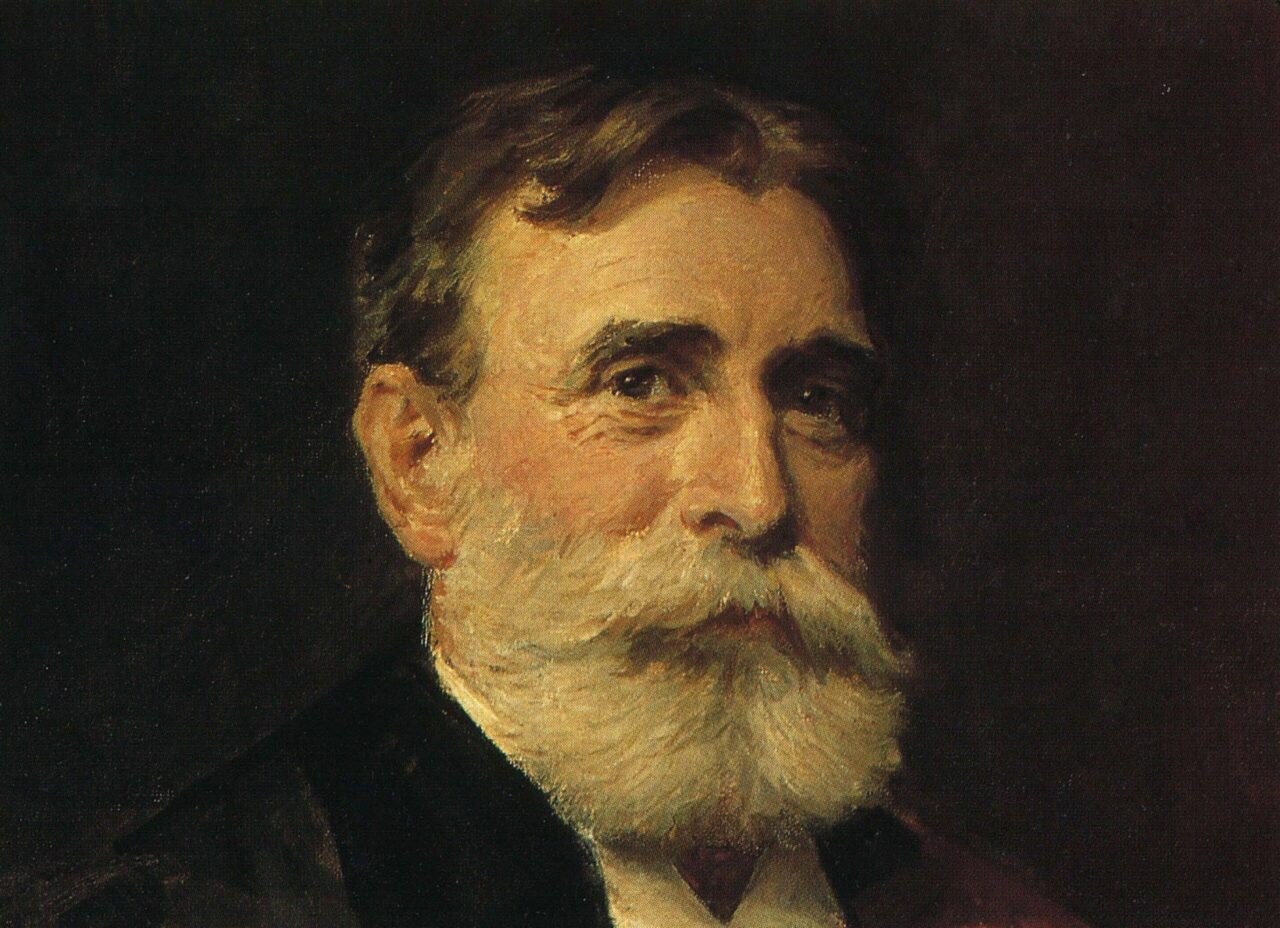

B. B. Warfield (1851–1921) was one of the great thinkers of the Reformed tradition. He was a lecturer at the old Princeton Theological Seminary in America, before Princeton shifted away from believing the Bible. With his colleague, A. A. Hodge (1823–1886), he is best known for framing the doctrine of ‘inerrancy’.

Inerrancy makes one central claim. Two qualifications quickly follow. Thus, in three points, inerrancy says the following:

- Everything said in Scripture is without error in all that it asserts to be true, whether in matters of theology, philosophy, history, science, and so on. Perhaps it is unfortunate that the doctrine is said negatively—‘without’ error. It is hard to put it positively in a neat way. ‘The entire truthfulness of Scripture’ is a mouthful. Perhaps ‘omniveracious’ or ‘omniveracity’ is the idea, but that feels strange.

- This entire truthfulness belonged to the ancient texts authored by the apostles and prophets rather than to the manuscripts available today (that is, to the extant Greek and Hebrew copies. The discussion was not about the English or other language translations, but the original language texts).

- Scripture’s statements are not to be taken in a woodenly literal way so that it is forced to affirm things that it does not intend to affirm. For example, common idioms should not be pressed to be statements of scientific fact. That the ‘sun rose’ (Gen 32:31) is a classic example of phenomenological language. Scripture does not err when it says this, for it does not mean to affirm it as a scientific fact. Mark Thompson, the principal at Moore Theological College, covers this very well in the ‘Warfield’ issue of RTR.

The question being addressed now is this: is inerrancy a doctrine found in the Westminster Confession of Faith (approved by the English Parliament in 1647)? That might look parochial. Here is a Presbyterian minister yet again writing about the Confession. To put the question more broadly, is inerrancy a historical, Reformed doctrine?

Still, the Confession was a consensus document from the end of the Reformation period, and nothing in chapter 1 on Scripture would have caused even a raised eyebrow from Reformed theologians across Europe. By focussing on the Confession, I can keep the topic manageable and save myself having to look through the entirety of 16th–17th century Reformed theology.

I am only going to address the topic in terms of the core idea of inerrancy—the claim that everything in Scripture is true (which is point 1 above). This hopefully makes things straightforward and avoids more contentious aspects. The below can then serve as a relatively easy introduction to the wider subject.

The question is this: does the emphasis on truth in the doctrine of inerrancy match what the Confession says about Scripture’s truth? What does the Confession say about the truth of the Bible? Before getting to that, I will speak about what the Confession and Warfield say more broadly about Scripture.

Contents

1. The Confession’s broader view of Scripture: sola Scriptura

Whatever Warfield and the Confession say about the truth of Scripture, it is hardly all that they have to say about Scripture. Starting with the Confession, its chapter on Scripture (ch 1) stresses various dimensions of sola Scriptura—ways in which Scripture is only.

The Confession’s very first sentence says that Scripture tells us how to have a saving relationship with God—and only Scripture can do that. We only find the way of salvation in Scripture, ‘those former ways of God’s revealing His will unto His people being now ceased’ (1.1).

The sola or only nature of Scripture emerges again when speaking of inspiration, the canon, and Scripture’s sufficiency and authority. There is even an only when it comes to interpreting Scripture, for the rule for interpreting one difficult passage is to see it in the context of the whole Bible (1.9). Only the Bible is needed to interpret the Bible.

We can pause there and say that even if the Confession did not directly address the subject of the truth of Scripture, it would still be a necessary implication. It is no good for Scripture to tell us the way of salvation if it is not telling us the truth. It is no good for Scripture to claim to be the ultimate authority that rules every facet of our lives if it is a fabrication. That would be as a road safety sign that led us over a cliff. The Confession implies Scripture’s truth everywhere in chapter one.

2. Warfield’s broader interest in Scripture: inspiration

Warfield and Hodge do not discuss the truth of Scripture in isolation either. Everything they say about infallibility is actually about inspiration. Scripture’s truth leads to the realisation that God is its Author and that Scripture is a special creation.

Hence, the title of the watershed article that they wrote in 1881 was simply ‘Inspiration’, not ‘Inerrancy’.1A. A. Hodge and B. B. Warfield, ‘Inspiration’, The Presbyterian Review 2, 6 (April 1881), http://www.bible-researcher.com/warfield4.html, accessed 30 March 2021. The aim was to demonstrate to people that the Bible was inspired. How can you help people see that the Holy Spirit moved ancient people to write God’s words? The truthfulness of the Bible seems to be somewhat provable, so people should be able to work backwards from a surprising level of truthfulness to the activity of God.

Inerrancy was primarily an apologetical doctrine.

For interest, that means that ‘inerrancy’ was primarily an apologetical doctrine used to defend Christianity. Hodge and Warfield were trying to engage with non-Christians. They also wanted to encourage people in their faith so that they would not reject the Bible as much of the Church had done. We can surely appreciate the goal.

I have some reservations about the argument, but I appreciate it, too. First, just because we can prove that some historical or scientific statements in Scripture are factual does not mean it is the Word of God. Much of what the authors of Scripture say is accurate simply because they were eyewitnesses of the events they describe.

Secondly, we cannot prove that everything in the Bible is true. We do not have that level of scientific and archaeological proficiency. That does not mean the Bible is wrong; it just means human knowledge is limited. There are always going to be things in Scripture that we cannot explain. The very first page of the Bible makes that obvious.

However, we do naturally sense the truth of the Bible—not its historical accuracy so much as its moral and spiritual truths. Scripture overwhelms us with its moral force. Why is that? Scripture’s truth accords with the spiritual awareness that God has built into us as human beings. We cannot help but know the voice of our Creator.

Thus, when we see the moral excellence of Jesus in the Gospels, we intuitively see our Creator. We see Him in the person of Jesus, and we see Him as the Author of the book we are reading. Some have dulled their minds and refuse to experience the Bible in this way, but still, Warfield and Hodge were onto something. The truth of the Bible does bring many to see the divine origin and inspiration of the Bible.

By the way, where did Warfield and Hodge get the idea that Scripture’s truth points to Scripture’s inspiration? They may well have got it from the Confession. Confession 1.5 says that the many ‘incomparable excellencies’ of Scripture, including its ‘entire perfection’, give ‘evidence’ that is it the Word of God. I prefer that word, ‘evidence’, to Warfield’s term, ‘proof’. It is more cautious and realistic. Still, the train of thought moves in the same direction. It is possible to read the Word and so to sense in some way that God is its Author.

3. Infallibility in the Confession

What does the Confession say directly about the truth of Scripture? The Confession uses the word, ‘infallibility’, or more accurately, it speaks of the ‘infallible truth’ of Scripture (1.5).

Some will immediately be alert to a problem. Since the late 19th century, ‘infallibility’ came to mean ‘unable to fall’. That is not a statement about truth but about the function of Scripture. The Scriptures never fail to accomplish their purposes. They never fail to bring people to salvation, or something like that.

That is, after all, what the word seems to mean in English. It has ‘fall’ in it. However, the term came from Latin. Infallibilitas means ‘unable to err’.Which itself comes from the word fallere, ‘to deceive…to put wrong, lead astray, cause to be mistaken.’2D. P. Simpson, Cassell’s Latin-English English-Latin Dictionary, 5th edn (London: Cassell, 1984), 240. One needs to grasp the Latin sense, not just rely upon what it sounds like in English.

The Westminster delegates intended to speak of truth when they used the word ‘infallible’. They meant that Scripture is ‘unable to err’. It is easy to demonstrate that they meant this.

First, there are their broader commitments. The Westminster ‘divines’, as ministers were called in 17th century England, belonged to a long theological tradition that prioritised knowledge and truth. As seen above, this is not all they want to say about Scripture, but there is every reason to believe that it is a major point that they would want to say about Scripture.

Some have complained that Warfield’s idea of ‘inerrancy’ sees the Bible through the dominating paradigm of truth, but the divines are not so different. It was just where 17th century Reformed theology was at, and the 16th-century Reformers, for that matter. Consider even just the opening lines of Calvin’s Institutes, which sum up the whole of Christianity as being about the knowledge of God and man. That itself was hardly a new idea, going back through the medieval theologians to the early Church.

One well-known expression in the Confession makes the point admirably. When defining what faith is—a key issue for Protestants!—they say:

By this faith, a Christian believeth to be true whatsoever is revealed in the Word, for the authority of God Himself speaking therein (14.2).

It is at the heart of Christian faith to accept Scripture as true. Clearly, Scripture’s truth is crucial for the divines.

To express how pivotal ‘truth’ was in the divines’ view of Scripture, a somewhat tedious, modern debate can be raised. The divines say something in 14.2 that not everyone would accept today. They claim that everything said in Scripture is an assertion of truth. It is not just that some expressions are about truth and other parts of the Bible do not have truth interests. Every expression is about truth.

Some today say that some parts of Scripture are true and other parts are not about truth—not untrue, but not about truth. For example, how is a piece of poetry in the Psalms about truth? Is ‘truth’ the correct category? How can it be said that a question in the Bible is true? A question, by definition, is not making a statement, so truth is the wrong way of looking at it (so it is said).

The divines characterise all parts of Scripture as true. That seems to be what they are saying, anyway. Truth is all-pervasive in Scripture (omniveracious!).

Truth is all-pervasive in Scripture.

Even if that is over-stressing the divines’ claim, it makes a good point. Every part of Scripture is truth from God and is to be believed. Even questions make truth assertions—and not only rhetorical questions. As a trivial example, ‘Where is the seer’s house?’ (1 Sam 9:18) means ‘I do not know where the seer lives, but wish to know, and would like you to tell me’. It the narrative, the wider assertion is that Saul spoke these words. Questions such as, ‘What is man that you are mindful of him?’ (Ps 8:4) are far more potent.

Our idea of truth needs to be stretched. Truth is not just historical and scientific—that would be a modernist and even atheistic view. There are religious, spiritual, or theological truths. There is a supernatural world and knowing the truth about it is vital! The Psalms are filled with truths, then. They speak the truth of God’s interactions with His people in history. They speak of His greatness, goodness, and nearness or distance. That the Psalms are poetry in no way means that they are not about truth. The central theme of the Psalms certainly is a truth claim, though not being verifiable by some scientific procedure: The Lord is King!

Hence, run your mind through Psalm 23 and tell me which expression in it is not true. ‘The Lord is my shepherd’, it says. One might say that ‘shepherd’ is an analogy, but once the analogy is understood, is it true? ‘I shall not want’—you need to have faith to see it, but with faith, we know it is true. Continue through the Psalm, and once accounting for metaphorical language, what else can we say but that it is true? Through the eye of faith, it is true. The only thing left to do is to apply these truths to our lives.

To return to the main point, if we are wondering what the Confession means by ‘infallible’, 1.5 is not the only place where the Confession uses the word. I am not going to evaluate each use now, but I quote them below. The thing to see is that it is hard to make all the uses mean ‘unable to fall’. Maybe that works for one of two phrases; it does not explain them all. However, ‘unable to err’ fits them all.

- The ‘infallible truth’ of Scripture (1.5)

- The analogy of faith is the ‘infallible rule of interpretation’ (1.9).

- God has ‘infinite, infallible’ knowledge (2.2) and ‘infallible fore-knowledge’ (5.1).

- The believer has ‘infallible assurance of faith founded upon the divine truth’ (18.2), and again, ‘infallible assurance’ (18.3).

Before moving on, something worth noting is this: the divines are not only saying that Scripture is true. They are saying it is unable to be anything but truth. It is ‘infallible’ or ‘in…able’ to err. Just stop and think about that. What could make a book unable to be in error? A newspaper article could be entirely truthful, but it could never have the property of being unable to in error.

Infallibility comes about for one reason only—because Scripture has a divine Author who by His nature is unable to err. The divines make a massive claim about Scripture’s truth nature and origin when they say ‘infallible truth’. As they put it themselves, the author is the God ‘who is truth Himself’ (1.4). God is truth (1.4); therefore, Scripture cannot be anything but truth (1.5).

4. Infallibility to Warfield

It is easy to demonstrate that Warfield’ followed the Confession’s view of Scripture’s complete truthfulness. This is because he used the Confession’s term, ‘infallibility’. Both Hodge and Warfield started out using ‘infallibility’, and Warfield always preferred it to ‘inerrancy’ (and Hodge gave ‘inerrancy’ more airtime).

‘Infallibility’ dominated for them because they were not making up a new doctrine. Warfield and Hodge saw themselves as merely defending and refreshing the Westminster doctrine for the modern context. In fact, it is almost inconceivable that Warfield departed from the Confession in something as important as this (and he vehemently denied that he had contradicted it). Warfield was steeped in the Confession. It is virtually everywhere in his writings. The Westminster Confession really was Warfield’s personal confession of faith.

Someone might ask, though, whether the two men meant ‘infallibility’ in the newer way of ‘unable to fall or fail’ rather than ‘unable to err’. This is readily resolved. One simple quote makes the point: infallibility means ‘absolutely errorless’.3Hodge and Warfield, ‘Inspiration’. Also see A. A. Hodge, Commentary on the Confession of Faith (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication, 1869), 59, where, in the place of assurance in the ‘infallible truth’ of Scripture, Hodge simply puts it that the Spirit ‘proves them true’.

Infallibility means ‘unable to err’.

Moreover, the functional view of infallibility, that Scripture never fails to achieve it purpose, really only emerged very late in the 19th century. Introducing the published form of C. A. Briggs’ famous or infamous inaugural address, A. B. Bruce spoke of ‘an infallibility of power to save’.4A. B. Bruce, ‘Introduction’, Inspiration and Inerrancy (London: James Clarke and Co., 1891), 4. The older view that connected infallibility to truthfulness was still current, though, even into the 1870s. The Roman Catholic Church at that time declared the Pope to be infallible: the ‘infallible teaching authority of the Roman pontiff’, as the First Vatican Council put it (1869–1870).5Decrees of the First Vatican Council, Session 4 (18 July 1870), 4.1, https://www.papalencyclicals.net/councils/ecum20.htm, accessed 30 March 2021. The Pope, speaking ex cathedra,was held to be ‘unblemished by any error’.6First Vatican Council, Session 4, 4.6. The Popes in this official mode did not and could not err, apparently.

Warfield commented on the Roman doctrine, and his comment again demonstrates that infallibility was about truth for him. He said that the Church held the Pope to be infallible because it had rejected the infallible Word.7B. B. Warfield, ‘Inspiration and Criticism’, Revelation and Inspiration (New York: OUP, 1927), 422. As Warfield saw it, people need to find truth somewhere. Since they refuse to find it in the Scriptures, in the ‘infallible’ Bible, they pretend it exists in other sources, even in an always-truthful Pope.

5. What does ‘inerrancy’ add or change?

Given the above, there is almost no need to discuss the word ‘inerrancy’. ‘Inerrancy’ does have some secondary connotations that some struggle with. Hopefully, though, it is apparent that its main idea is really only an alternative (and clearer) way of saying ‘infallibility’.

Sometimes it is the wider context of Hodge and Warfield’s thought that stops people from accepting ‘inerrancy’. That would be ‘guilt by association’ (e.g. they were rationalists; therefore, everything they said is wrong). Wider issues aside, though, the central claim of inerrancy is just standard Reformed theology, or actually, historical Christianity.

There is one thing that ‘inerrancy’ in its main idea loses in comparison with ‘infallibility’. The word technically loses the ‘unable’ to err dimension of infallibility. Warfield and Hodge certainly did not reject the idea that Scripture was ‘unable’ to err, though, so this is no problem.

That trivial point occurs only because it is hard to find an English word that neatly speaks of the Bible’s truth. ‘Infallibility’ is a great term—if you know Latin. It becomes even more confusing once the critical scholars get their hands on it and deliberately change its meaning. If the best word is ‘omniveracious’ (all truth), we will be in trouble, since it sounds too similar to voracious (from a Latin word for devour).

Is ‘infallibility’ or ‘inerrancy’ the better word to use today? The choice seems to be between:

- An unclear word (infallibility) with a solid historical connection (the Westminster Confession).

- A clear word (inerrancy) with what some see as a poor historical connection (rationalist, American fundamentalism).

Perhaps both words should be used together. Would that balance out the weaknesses of each?

Infallibility – define it when you use it!

Infallibility, as the less clear term, needs more care when used. My plea would be to make sure you define it when you use it. If you do not define it when you use it, and I am in earshot, I am probably just going to ask you what you mean by it (although does defining it every time it is used defeat the point of using the word?). Inerrancy also may need some qualification, but the reason why has not been discussed in this article.

6. The value of truth

Before concluding, I hope it is understood just how pastorally and personally valuable the doctrine of infallibility or inerrancy is. Perhaps we do not realise just how important truth is to us as human beings. We are drowning in lies in our society and often lies that we individually create for and about ourselves. How we suffer when we do that. If we were built for God and made in the image of God, we were built for truth. Every lie takes its toll within the human spirit in terms of anxiety, guilt, anger, pride, fear, and despair.

Every lie takes its toll within the human spirit.

Those who downplay the always-truthful nature of Scripture do the Church a great disservice and deal a psychological blow to so many. Do not undervalue the truthfulness of Scripture! Instead, grab hold of it as a lifebuoy to a drowning person. We do not need inerrancy just so that we can be right about everything; we need inerrancy so that we can live.

7. Conclusion

‘Infallibility’ in the Confession speaks about the complete truthfulness of Scripture. Hodge and Warfield knew the term from the Confession and understood it in the Confession’s way. The term did not mean that Scripture was ‘unable to fall or fail’ but ‘unable to err’. It was a way of affirming the entire truthfulness of Scripture.

This older sense of infallibility carried over into the new term, inerrancy. Inerrancy is a more intuitive word in English for expressing the truthfulness of Scripture, and so at that level has a great advantage. The older sense of infallibility is largely obscured today, with a decline in understanding Latin, and because critical scholars deliberately shifted the meaning of the word to avoid speaking about Scripture’s truth.

This article has taken just a first step to comparing the Confession with Warfield and Hodge’s view of inerrancy. The easy part has been covered. The difficulties really only begin as this article ends.

Both the Confession and Warfield give us insight into something very precious. We have the only-able-to-be truthful Word of God. How important this is. Since Scripture is true, we have a true salvation, and we know the true Christ. When we encounter the Scriptures, we encounter a miracle. A ladder of truth drops down out of heaven for us and calls us upwards. As we read, He imparts Himself to us. We encounter, by the ministry of the Spirit, our God who is truth itself.